Concepts and Techniques of Aikido

Morihei explained how the “Way of ai-ki” evolved, and how his ideals were distinctive from other martial interpretations. “I have studied many systems of combat until now including Yagyu-ryu, Shin’yo-ryu, Kito-ryu, Daito-ryu and Shinkage-ryu. However, aikido is not an amalgamation of these.” Although the term ai-ki is common throughout these classical styles studied by Morihei, they are often mistakenly confused as being identical in substance. This is especially the case with Daito-ryu, and in some authoritative Japanese encyclopedias, no distinction is made between aikido and Daito-ryu, aiki jujutsu . ”I decided to name the ‘Way’ I have created aikido. There exists a fundamental difference between the ‘ai-ki’ espoused by classical warriors and my interpretation.”

Morihei explained how the “Way of ai-ki” evolved, and how his ideals were distinctive from other martial interpretations. “I have studied many systems of combat until now including Yagyu-ryu, Shin’yo-ryu, Kito-ryu, Daito-ryu and Shinkage-ryu. However, aikido is not an amalgamation of these.” Although the term ai-ki is common throughout these classical styles studied by Morihei, they are often mistakenly confused as being identical in substance. This is especially the case with Daito-ryu, and in some authoritative Japanese encyclopedias, no distinction is made between aikido and Daito-ryu, aiki jujutsu . ”I decided to name the ‘Way’ I have created aikido. There exists a fundamental difference between the ‘ai-ki’ espoused by classical warriors and my interpretation.”

Morihei met with Takeda Sokaku ( 1859-1943), the “reviver” of the Daito-ryu, in February 1915, when engaged in development work in Hokkaido. He immediately became Sokaku’s student, training under him whenever he could. On March 1916, Sokaku rewarded Morihei with a teaching license and certificate of mastery in the school. Morihei’s relationship with Takeda Sokaku was different to any he had with previous jujutsu teachers. Morihei remained a dedicated student of Takeda Sokaku until he passed away in 1943.

A newspaper reporter posed a question to Morihei in later years. “Did you discover aikido when learning Daito-ryu?” Morihei replied, “No. It would be more correct to say that Master Takeda opened my eyes to budo.” He taught Morihei if studying the combat arts, then one must do all in his power to win. Morihei, however, started to have misgivings about the idea of winning at all costs. This skepticism guided Morihei’s a transition from “jutsu” to “do”, i.e. from an emphasis on winning through technical proficiency to a ‘Way’ of personal cultivation.

“The moment I was awoken to the idea that ‘the source of budo is the spirit of divine love and protection for everything’, I couldn’t stop the tears flowing down my cheeks. Since that awakening, I have come to consider the whole world to be my home. I feel the sun, the moon and the stars are all mine. My desire for status, honor and worldly possessions has completely disappeared. I realized that ‘Budo is not about destroying other human beings with one’s strength or weapons, or annihilating the world by force of arms. True budo is channeling the universal energy (ki) to protect world peace, to engender all things fittingly, nurture them and save them from harm.’ In other words, ‘Budo training is to protect all things and nurture the power of unconditional divine love within.'”

Morihei had a religious temperament and he often made reference to the word “kami”, meaning ”divine” or “gods”. His intention was to discern between martial techniques for combat and budo for peace and harmony, the distinctive fundamental spirit of aikido. In simple terms, he deemed it more important to find common ground and accord with others, than using strength and fighting to overcome them.

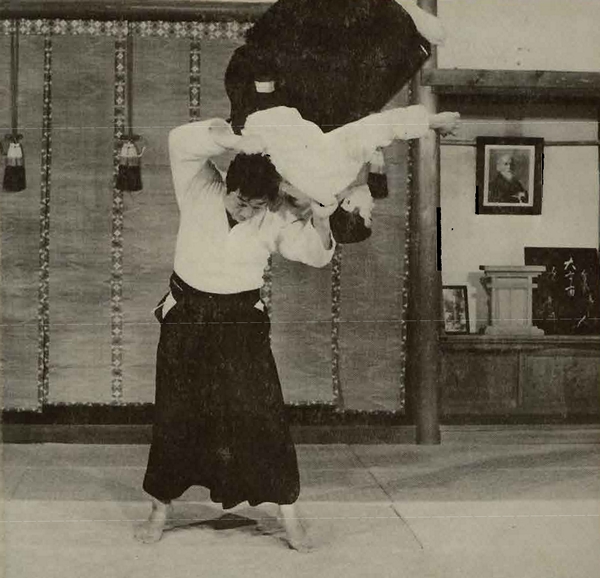

As the premise for aikido is accord and harmony, there are no offensive techniques used to initiate the engagement. The uke acts as an aggressor and initiates an attack, and the tori uses his or her techniques to defend. Because of this, there are no matches in aikido, and no competitive randori (free sparring).

‘There are some who reject the idea of ki as unscientific. Some people also use the term with great frequency, and it has a different meaning for each individual. Morihei believed that ki was the energy that bound body and soul together. Ki is the source of human vitality and is the energy that flows through all natural phenomena. In aikido, all techniques are based on circular motion. You throw your opponent by maneuvering in a circular manner. Spherical movement allows the practitioner to avoid collision with opposing forces and facilitates harmony. As movements are smooth and devoid of erratic interruptions, ki is able to flow smoothly through the entire technique without diminution.

In order to draw a circle in the technique, the center point must be fixed and unwavering, just like the central axis of a spinning ball. Although the ball is rotating at high speed, there is little superfluous movement, and it looks as though it is perfectly still. The moment it is touched by another object, however, it is repelled by the latent power

demonstrating “stillness within movement” (sei-chu-do).

Morihei described this condition as “The principle of sumikiri”, or total clarity of body and mind. ‘There is a well-known story of when Morihei became aware of this notion. In 1923, the Morihei traveled with Omoto-kyo leader Deguchi Onisaburo to Mongolia. While traversing a mountainous region, the group was attacked unexpectedly by

bandits. Bullets hailed down on them from all directions, and just as Morihei thought all would be killed, he suddenly he felt composed and focused. He somehow managed to avoid being hit by any bullet by sensing where it was coming from, and dodging them on the spot by turning his body without jumping out of the way.

This tranquillity is described as “sumikiri”. He later described this experience of sumikiri and sei-chu-do as enabling him to sense hostile or murderous intentions in others. Although holding mysterious attraction for many people, it must be remembered that this remarkable episode came after many years of austere training in the study of the imperative substance of maintaining an immovable center.

The first step in keeping “centered” is to breath from the seika-tanden which is located just below the navel. Controlling breathing enables the natural rhythm of ki to flow throughout the body in complete synchronization with universal energy. The seika-tanden is also referred to as the “Hara”. ‘The term “hara ga suwaru” (the hara sits) is used to describe somebody who is calm and serene. Such mental imperturbability and inner-strength are achieved through training the physical body. Before training commences, aikido practitioners often do an exercise called ‘furitama” which is intended to focus ki. This and respiratory exercises are very important in the study of aikido.

In aikido, those who train for many years learn to conform to and not oppose natural laws, nor do they try to control things forcibly. They exhibit what is called “shizentai”, a state of being which is natural and relaxed. As long as the practitioner is able to maintain the constant unimpeded How of ki, he or she will be able to perform movements

harmoniously and naturally, even if they do not seem to be circular. Morihei explained the never-ending transition in aikido.

“As you know, aikido techniques are constantly changing year by year. This is an essential principle of aikido. On such occasions, I stand with you as a member of the dojo and continue to conduct research. There is no set form in aikido, and all aspects are teachings of the soul. One must never become preoccupied just with form lest you become unable to execute subtle movements.”

In this way, if the practitioner is able to fix the center of mind and body, ki will flow unconstrained, and he or she will be able to perform a myriad of technical variations. This is what Morihei meant by there being “no set form in aikido”. As long as the principle of ai-ki is present, then all techniques are in accordance with aikido’s philosophy.

The center is maintained in both physical movements and in the mind. By cultivating the center over many years the trainee learns to move adroitly both physically and mentally and will learn how to avoid confrontations with others. Ultimately, the student of aikido will learn to embody the mental composure and physical dexterity to deal effectively with whatever situation he or she is faced with. The Aikido practitioner also learns respect for other people, and to value harmonious relations.

Kisshomaru made the comment that “If budo is not able to be utilized by people living in the modern age in the course of their everyday life, then surely it has no purpose.” Although its philosophy is deep and profound, aikido is not a difficult budo to learn. However, the benefits to the individual and society are potentially great. Paradoxically,

by learning combat techniques, the aikido student is given access to a world that is pacifistic and profound. In Morihei’s words:

“True budo is to discipline the self and to lose the will to fight … It is to lose all enemies, and is an absolute path for self-completion. The martial techniques provide discipline for the journey of uniting the spirit and the body through channeling the laws of heaven. Techniques provide the medium for ‘Way’.”

To achieve the stated objectives of aikido requires that techniques must not be studied half-heartedly. There is no point in which a waza, a technique, can be called perfect. With continued training, waza improvement has no bounds, nor does the potential for nurturing one’s qualities as a human being.

“To purge the self of maliciousness; to find harmony and to be at one with the natural order of the universe … That is to make the mind of the universe your own mind. What is the mind of the universe? That is the great love that is found in every corner of the universe, in the past and the present. .. True budo is the movement of love. It is not to kill or fight, but to let all things live, grow and flourish. ”

This philosophy exhibits the culmination of aikido ideals. The most important aspiration in aikido is to rid oneself of enmity and the urge to vanquish one’s opponent.

“It is a grave mistake to think that budo is about being stronger than your opponent and that you have to defeat him. In true budo, there is no enemy. True budo is to become one with the universe. It is to be united with the universe’s center. In aikido, we do not train to become fierce or to defeat opponents. Instead, we strive to make even a small contribution to peace for all people in the world. That is why we must harmonize with the center of the universe.”

Aikido training consists of the repetition of basic techniques with many partners of differing size and strength. The Aikido practitioner subdues feelings of aggression. Instead, the goal is to work with each other and to react naturally with the flow of the partner’s energy and technique, rather than against it. These principles also manifest in the personality of the practitioner. Exhaustively studying the basic techniques is the medium in which the practitioner learns to be respectful and appreciative of all things, and become a person of sincere and honest character. “The point is not to fix the other person, but to repair the self. This is ai-ki. This is the function of ai-ki and the duty of

each individual.” Aikido is a way of self-completion which requires humility. Trainees engage each other with earnestness devoid of any intentions without defeat or harm others. To embody these principles through aikido, one must actively train. Practitioners are taught to train in accordance with the following three rules:

- Continuation

You will never be able to master aikido without ongoing training. When you have trained long enough to be proficient in the techniques, the joy and depth of aikido will become more apparent and will provide even greater impetus to continue.

- Compliance

Follow the instructor’s advice respectfully, and observe his or her techniques with an open mind.

- Curiosity

Even if you believe that you are executing the technique the way you were taught, it is natural to encounter difficulties in the beginning. You should try to discern why or how your technique differs from that of the instructor. Being compliant, but simultaneously curious and inquisitive, is the fastest way to learn.

“The path of ai-ki is boundless. I am seventy-six years of age but am still learning. In aikido, heaven and earth are the venues for study. There are no horizons on the ascetic path of training and no end. Training is a lifelong pursuit and is a way that continues for perpetuity. Thus, those of us who aspire to walk down this road must train in order to absorb the great love of heaven and earth in our hearts, and undertake to care for all things in accordance with the true path of budo.” (Ueshiba Morihei)

Source: Nippon Budokan (2009) BUDO, The Martial Ways of Japan, Japan.